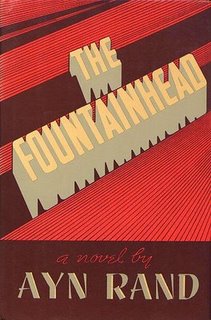

I was 18 when I discovered philosophy. I asked my high school librarian for books to stretch my mind. She picked a couple, but only one stayed with me. It was The Fountainhead, by Ayn Rand. This book did more than any other to open me to the world of ideas.

It is the story of Howard Roark, an architect who insists on following the integrity of his own vision. Against all outside obstacles, both material and ideological, he creates according to the standards he chooses. The story enthralled me. Not the kind of hero I expected, Howard Roark was purely self-interested. And, to my amazement, he was good. The Fountainhead did indeed stretch my mind.

The seven lessons I learned about values:

A man’s fate depends on his approach to values.

The book contrasts Howard Roark, a man who chooses his values, with Peter Keating, a man who pursues whatever other people do. Rand coined a term for Keating: a second-hander. The novel showed me the long-term consequences that must logically follow from each man’s approach.

It is possible to seek values uncompromisingly.

Roark’s amazing quality was his purity of purpose. What he wanted, he wanted. His commitment to his own values protected him against compromise at all stages of his career. For the sake of his own standards he was willing to walk away from the academy, from desperately needed contracts, and even from a woman who was not yet ready to believe his dreams were possible. By the end of the novel I saw that Roark’s commitment to his values had no limits.

If a man will be a value-seeker, he must be one by choice.

Roark worked for his values because he himself had chosen them—they were his own values. For this kind of man, of course the commitment to values would have no limit, for what else could a man commit to than his values? Not so for Peter Keating. If one selects values without reason, what reason could there be to uphold them? Not choosing; that is a choice. Because he defaults on choosing and upholding his values, Keating is undone.

To be a value-seeker, a man must think for himself.

Roark took responsibility to choose his values; this meant thinking for himself. For Roark, the judgments of other people never took a fundamental importance. Like Joan of Arc in George Bernard Shaw’s play, Roark would have asked, “What other judgment can I judge by than my own?” That is the motto of the individualist.

Thinking about one’s own values is selfish, but it is good nevertheless.

Roark thought for himself because he recognized that reality is real and the wishes of others do not change it. He assumed responsibility for his own choices, based on his own reasoning, based on the facts he grasped. “When I see something, I see it.” That is the motto of Rand’s heroes. When I first read The Fountainhead I knew it was right to commit to the truth and to rationality. But I learned a new connection: to think for one’s self is to value one’s self. Therefore, thinking is selfish, and selfishness requires thinking.

Selfish values are not evil.

I had already accepted that it is proper to follow reason. But I learned that this commitment entails a commitment to value my own life. Thought is not an end in itself, but a means toward action—toward reasonable action—action that supports one’s own life. The very function of thought is selfish. We think, we value, we choose, we work, and thus we live. That is Howard Roark’s story. His selfishness did not mean he took from others or trampled them. In fact, his selfishness made him self-sufficient, productive, and proud. Roark was selfish, and he was good.

Properly, all values are selfish values.

I learned the connection between the value and the valuer. There can’t be one without the other. All proper values are values to an individual, for that individual. It is proper to value selfishly. That’s what it means to live.

Selfishness doesn’t prevent us from loving others or desiring the best for them. In fact, selfishness guides us in whom to love, and it gives us the reason to love others—because we see them as a personal value.

All proper values are thus personal values. This radical idea greatly clarifies questions of personal motivation because it means my motivation can only be my motivation. To say a person “ought” to do something is to say “it is in his interest” to do something. That is all an “ought” can ever be. Thus there is no separation between the moral and the practical; “the good” is always “the good for someone, for some purpose.” Morality can never require a person to choose that which is not in his own best interest.

Morality is selfish.

The only reason for me to do something is that there be a reason for me (for my interest) to do it.

The Fountainhead taught me to uncompromisingly seek my own values. As a Christian, this shocked me. Does it shock you? Ask yourself: when you think of morality, do you think mainly about laying down values and denying yourself? Or do you think about gaining a reward?

Then Jesus said unto His disciples, “If any man will come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow Me. For whosoever will save his life shall lose it, and whosoever will lose his life for My sake shall find it. For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul? Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul? For the Son of Man shall come in the glory of His Father with His angels, and then He shall reward every man according to his works” (Matt 16:24-27).